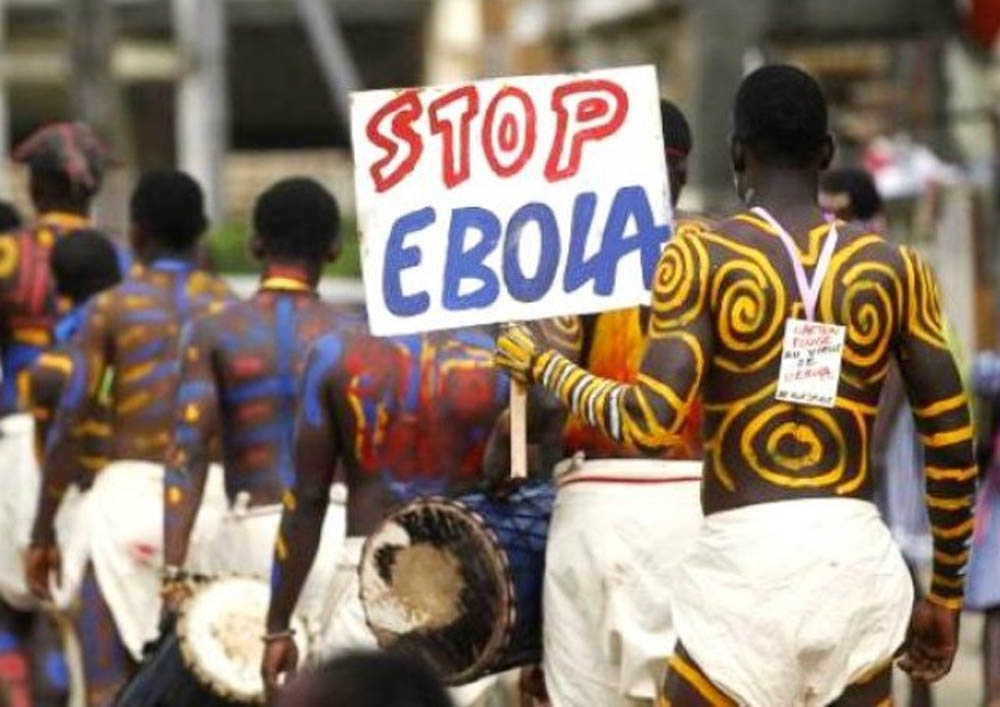

The Ebola outbreak has claimed almost 5000 lives since March. A vast majority of lives have been lost in West Africa, with Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea facing the worst hit. Even though WHO has declared Nigeria Ebola free, there is as yet no vaccine or even a specific treatment for the virus, which has a dismal survival rate of 37%.

[contentblock id=1 img=adsense.png]

This infection produces a range of mild to deadly reactions in people, from complete resistance to moderate to severe illness, followed by recovery and then to excessive bleeding, organ failure and death. Like HIV, Ebola is not airborne. Touching the blood and body fluids of a patient, as well as contaminated objects like needles, transmits the virus. Even though Ebola has mostly affected West Africa, with only nine reported cases in the US and a few sporadic ones in Europe, most developed countries have stepped up their response to the deadly virus by implementing travel restrictions and mandatory quarantines of people returning from Ebola-stricken countries.

Interestingly, whereas a large part of the debate in western countries centres on implementing adequate measures to contain the virus without turning caregivers and patients into pariahs, in Pakistan, the government evidently doesn’t think we are actually at any risk from this deadly disease at all. How else do you explain the fact that the government’s response to the virus has largely focused on bureaucratic measures involving the establishment of ‘steering committees’ and ‘focal persons’, which sound good on paper but are fairly ineffective without the mobilisation of resources and some kind of accountability.

Most airlines operating in the country’s airspace are not complying with national (Personal Declaration of Health and Origin Rule), and international requirements (International Health regulations 2005, International Civil Aviation Organisation Regulation) of collecting information on passengers’ health status. Health forms are not always given out to passengers and even if they are duly filled, they are often not collected by airport authorities. Some airlines like PIA and Shaheen Air International have reportedly refused a medical examination of their food handlers. Moreover, airport health departments are largely underfunded and understaffed.

The department at Karachi airport has been denied a room in which to interview and examine incoming international travellers and an office at the cargo complex to examine goods due a lack of cooperation from the Civil Aviation Authority. The problem of screening travellers at major airports is only the tip of the iceberg. What about those entering the country through numerous land and water routes? And what happens if a patient is suspected of being infected? A quarantine facility set up in Bhitaiabad, Karachi for Ebola patients lacks the basic protective measures for an effective isolation, defeating the whole purpose of setting up quarantine.

[contentblock id=2 img=gcb.png]

Refusing entry to suspected patients, as has happened in one reported incident, is not enough to contain the virus. Even if there are no symptoms of the disease at the point of entry in to the country, people with a history of travelling to infected areas need to be periodically monitored in case they develop symptoms. An infected person can escape detection at an airport screening if they take fever reducing medication a few hours before landing. That is if we have functional screening processes at airports, which currently we do not.

This kind of negligence is disturbing given that most experts have predicted that there will probably be a few cases in Asia before the year is out. China is particularly vulnerable due to its vast trading ties with West Africa. A large number of Chinese nationals working in Africa are due to return home for the Lunar New Year, in the middle of February next year. However, China has an experience in coping with contagion, given the SARS outbreak in 2003.

Next door, India has an effective tracking and control mechanism used to eliminate polio. In spite of these advantages, these two countries, which are at the highest risk of Ebola in Asia, have been preparing their medical systems for the new threat. Ironically, Pakistan, who cannot even get a handle on polio, is obviously not too bothered – even though an outbreak in the neighbourhood will almost definitely transmit the disease to our soil. And let’s not forget the thousands of Hajis currently streaming back into the country after socialising with pilgrims from across the world.

The emergence of sporadic cases of the Ebola virus does not necessarily lead to outbreaks as long as the necessary precautions are put in place. However, the key to Ebola control is to break the chain of contact. In the absence of a vaccine and effective treatment, protective measures are the only way to prevent the spread of this disease. While the news of recovering patients in the US and the recent declaration of Nigeria as officially Ebola-free are heartening, we have to remember that the US has state of the art isolation facilities while Nigeria deployed personnel, technology and management methods used to combat polio to detect Ebola cases,

Trace contacts and implement quarantines. We can’t even eliminate polio, a disease that not only has a vaccine but is also far less deadly and infectious than Ebola. Forget polio, we can’t even manage dengue, a disease that follows predictable seasonal cycles and doesn’t spread by human contact. Imagine the devastation wrecked by something like the Ebola. Pakistan’s experience of viruses, with its densely populated cities and towns and abysmal medical infrastructure,

[contentblock id=3 img=adsense.png]

Will probably be similar to that of Liberia and Sierra Leone where the epidemic has reversed years of economic gains. Even the formulation of a vaccine is not a guarantee against an outbreak. Medicines and vaccines are only as good as their availability, as amply demonstrated by our inability to eradicate polio. In the case of Ebola, prevention must be prioritised. We urgently need to mobilise our resources to detect and isolate cases because we are hardly equipped to handle a full-fledged outbreak. – tribune