They are the bodyguards of the Himalayas,’ Pappu told me as I watched the clouds rolling in over the glistening white peaks. ‘They protect the eternal snows from the fierce sunlight.’

He was evidently not just a guide but also a poet. Self-taught and only 21, Pappu accompanied me and a small group of friends on a week’s trekking in the foothills of Nanda Devi in north-west India.Few tourists visit this area but I was enjoying a unique holiday experience, staying with local people and immersing myself in village life in the Saryu and Pindar Valleys in Uttarakhand, a remote corner of the country bordering Tibet and Nepal.

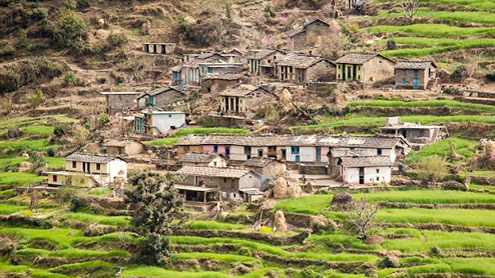

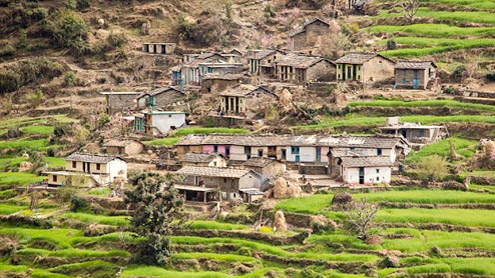

Just reaching the village of Supi for the start of the trek turned out to be a marathon journey. Following a flight from London to New Delhi, I took an overnight sleeper train, then a long taxi ride to the Khali Mountain Resort. This beautiful colonial estate set among pine trees was once used as an ashram by Mahatma Gandhi.After an overnight stay at the resort, I travelled a further six hours by road, culminating in a white-knuckle ride along a dirt track with sheer drops into the gorge below.By the time I arrived in Supi, I had been travelling for 40 hours. Still, it was worth the effort, for the views were staggering. Terraces of vivid green barley and yellow mustard plants cascaded down the hillsides, while high above, dazzling pinnacles of ice glittered in the sunshine.

My trip was organised through Village Ways, a small tour operator which has helped isolated communities in this region by contributing funds to convert traditional homes into guest houses and create much needed employment. Many local people now work as cooks, cleaners, porters and guides.Each day, our group would trek with Pappu for six hours or so from one village to the next.Our accommodation along the way was simple: the two-storey whitewashed buildings had five bedrooms at most, all with roughly hewn walls, beamed ceilings and carved wooden shutters. Some had en suite bathrooms while others were more basic, with outside latrines and buckets of hot water for washing.

Electricity was spasmodic, so solar lanterns were used when the power cut out.Once the sun set and temperatures plummeted, we would huddle around a wood-burning stove in the cosy dining room before taking piping hot water bottles to bed. We lived on the staple diet of chapatis, dahl and rice supplemented with home-grown organic vegetables.My favourite meal was the afternoon snack waiting for us at the end of a long walk: spicy pakora (a type of fritter) served with masala tea. Drinking water, which was boiled and purified in the kitchens, ended up with a distinctly smokey flavour from the open hearths.

Life in the hill villages has remained much the same for hundreds of years.On our first morning we explored Lower Supi, where a blacksmith was hammering metal bars into horseshoes over a charcoal brazier, and women in colourful saris were scything the crops. There was just one small shop, where the owner, Chandra Ram, showed me slippers and hats he had spun from sheep’s wool and knitted himself.Wide-eyed toddlers hid shyly behind their mothers’ saris but the older children followed us everywhere, keen to practise their English and also to have their photographs taken.

It was the Hindu New Year and celebrations were in full swing, with children rushing from house to house carrying poles festooned with flowers and eagerly awaiting presents of sweets and biscuits. I was soon caught up in the excitement, bowing my head and clasping my palms together to wish everyone well with the greeting ‘Phoolo phalo’.Elderly women offered me jaggery, a delicious home-made fudge, while I scattered petals in their doorways. The hospitality was overwhelming – smiling faces greeted us everywhere.

At Jhuni, near the Tibetan border, an aspiring guide called Tara invited us into her mud-brick home. We sat on woven mats on her flagstone terrace, sipping herbal tea while dogs lay sprawled in the sunshine and young goats gambolled beside us. Cows also ambled past, their brass bells jangling, on the way to pasture. It may have seemed like an idyllic rural scene but it masked a harsh existence.

Later in the trip, the whole community turned out to meet us at the village of Khal Jhuni. We were the first people to stay at its new guest house and a huge party had been organised to mark the event.Local women dressed in black skirts and colourful shawls welcomed us, and one daubed a red spot, or bindi, on my forehead for good luck before placing a garland around my neck. Joining the villagers, we danced along the narrow pathways to the sound of bagpipes and drums.

The next day, we set out on deserted trails leading up through pink and red rhododendron forests where brilliantly coloured butterflies feasted on the nectar. We scrambled over tangled roots above wooded ravines and stepped gingerly across mossy stones bridging waterfalls.As I stopped to catch my breath on the steep stone steps, our female porters raced ahead, laughing and chatting to each other.I felt guilty to see a slender young woman with my kitbag slung across her shoulders, but Pappu pointed out that they transport at least four times as much when they collect fodder for their animals.

The highlight of the trip was a night at the Jaikuni camp, which is located at nearly 10,000ft on a high ridge above the snowline. The spacious tents were equipped with proper beds and down sleeping bags.I woke at dawn to an awe-inspiring sight.The entire Nanda Devi mountain range was spread out in front of me, its colossal walls of snow and rock turning golden in first rays of sunshine. The air sparkled with ice crystals and high above, a Himalayan griffon glided on the thermals, its wings resembling giant black fangs.

Heading further up the ridge, we trudged through snowdrifts almost 3ft deep. I followed Pappu, stepping in his footprints to avoid sinking up to my thighs. Animal tracks crisscrossed the terrain and I paused to study a pawprint. ‘It might be a leopard,’ said Pappu.We saw no further sign of it but as we descended into the Pindar Valley, I saw a flash of red in the undergrowth.To my amazement, a giant flying squirrel was cowering in a hollow of a tree trunk. Even the guides were baffled to see this nocturnal creature in daylight.

On the final morning we trekked down the hillside for more than an hour to the nearest road. As our taxi drew up, I realised that it was the first vehicle I had seen since my arrival.Clambering aboard to start the long journey home, I glanced up for a last view of the mountains. They stood proud against a cornflower blue sky.Obviously the bodyguards were still asleep. – DailyMail