That one leader after another from Pakistan’s ruling party has been alleging a ‘conspiracy’ to delay elections indicates that this is now the party’s line of reasoning irrespective of whether there is any evidence to match the claim.

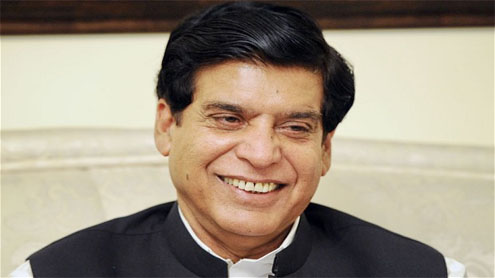

The fact that the government in approaching a full term in office hardly squares with assertions of plots to derail democracy.All the leaders crying conspiracy ignored the fact that by setting a date for elections their government could, in one stroke end all rumours and thwart the so-called ‘plot to put off polls’. The prime minister, Raja Pervez Ashraf, also joined the conspiracy chorus contradicting an earlier statement in which he pronounced that all stakeholders were committed to democracy — judiciary, army and political parties.

Why have government leaders been droning on about conspiracies? Is this out of habit or paranoia? Is it a ploy to divert attention from the real issues and troubles afflicting the country? Does this represent a flight from reality? Or is it a combination of all of the above? Government supporters would argue that their party’s stance is informed by its historical experience. But there may be other more persuasive reasons for this.

As the elections draw closer, the PPP leaders have stepped up the conspiracy rhetoric. This strengthens the impression that the narrative seems more a stratagem than fear — a ploy to keep public and media attention as distracted as possible from the government’s underwhelming record in office. What better in pursuit of this aim than to have TV talk shows embroiled in debating tantalizing and shadowy plots and sow confusion in opposition ranks– all the while taking pressure off the government.

Usually with elections around the corner, the incumbent party tries to steal a march on its rivals by marshalling out its accomplishments to offer voters a compelling rationale for why it should be voted back to power. That the PPP leaders are directing their energies to fighting off ‘conspiracies’ suggests they don’t have any achievements to present to the people.Government conduct on other fronts too shows similar tactics to deflect focus away from issues uppermost on the public agenda — weak governance, widespread corruption, a deteriorating economy, breakdown of law and order and the worsening power crisis. The latest example of diversionary tactics was the proposal by a government appointed parliamentary commission for a new province in Punjab.

The controversy over this pushed the country’s pressing challenges into the background and ensured that political debate in Parliament and the media swirled around the issue of new provinces. This reinforced the lack of attention given to issues weighing heavily on the public mind.So did the two major parties’ preoccupation, in gearing up for elections, with political maneuvering and wheeling and dealing. The focus of this activity was on enticing ‘electable’ candidates to switch loyalties from other parties. Political expediency ruled the day not principle or articulation of party positions on key issues of public policy.

The near-exclusive focus on machinations to persuade local power holders to change loyalties turned pre-election politics into intra-elite competition that had nothing to do with the problems faced by the people and their concerns. Cynics would argue there is nothing new about transactional politics or changing allegiances. But the question is whether this is compatible with the widespread yearning for change in the country for which the evidence is overwhelming.

Meanwhile, the assumption that recruiting ‘influential’ candidates is all that major parties need to do has been called into question by an opinion poll conducted by the International Republican Institute. When respondents in the Punjab sample were asked what would determine the choice of candidate they will vote for, 40 per cent said the party stance on issues. This indicates that a significant number of people give precedence to issues over personalities.

In evolving their campaign strategies political leaders would benefit from carefully examining this survey’s findings. 70 per cent thought their personal economic situation had worsened in the past year. Asked to name the single most problem facing Pakistan 65 per cent mentioned issues concerning their economic well being – inflation, unemployment and power shortages.The survey only confirms what is already well-known about what the public wants from its rulers – better governance and solutions to the country’s problems. It is these issues that matter to people not unsubstantiated ‘conspiracies’ or promises for new administrative units by those who have failed to competently run existing ones. – KahleejNews