FOR SEVERAL months last year, I was at the receiving end of occasional emails that conformed to a particular pattern. They all began with a reasonably uncontroversial critique of the political process in Pakistan, and they all concluded on the same note: that one man had all the answers.

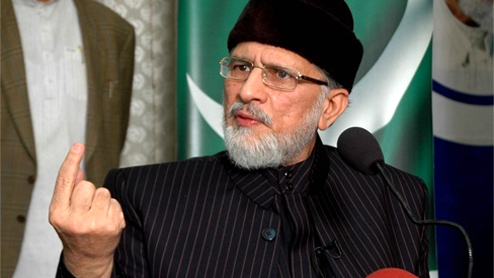

His name? Maulana Tahirul Qadri. I’m sure many other journalists were bombarded with similar missives as part of what was clearly a well-orchestrated electronic mailing campaign.Upon arriving in Pakistan just after the middle of December, I discovered there was a lot more to it. The vast majority of rickshaws in Lahore prominently bore the maulana’s visage on their backflaps, accompanied by an exhortation to flock to his Minar-e-Pakistan rally on December 23. Innumerable banners and hoardings bore his message: it’s not the political process but the state that deserved to be preserved.

Qadri’s statements on the eve of his public meeting provided some cause for concern. He noted, for instance, that there was a time when the United States was keen to provide aid to Pakistan for building dams, but the advent of terrorism had compelled it to resort to drone attacks. He uttered not a word about the circumstances, let alone the US role therein, that had spawned the terrorists.

It was also notable that he dated Pakistan’s troubles back to 1989, thereby implicitly sanctifying the previous dozen years of ruthless military rule wherein lie the roots of so many of the nation’s subsequent dilemmas.He also took considerable pride in recounting that he had been invited to address US military graduates. Even more disconcertingly, he proclaimed himself a Nobel Peace Prize nominee who had barely been pipped to the post by the European Union. There was no clear explanation of why he might have been deemed a worthy recipient.

The Minar-e-Pakistan gathering was numerically impressive, even though the claim of two million attendees was, in all likelihood, a considerable exaggeration. Contrary to the impression Qadri might have given, though, he did not quite pull a rabbit out of his distinctive headgear. What he produced bore a closer resemblance to a red herring.Equipped with a meticulously flagged copy of the national constitution, he read out a selection of provisions, allowing three weeks for a dispensation that would magically do away with exploitation, feudalism and corruption within 90 days — or more. If not? Well, then the nearly-Nobel maulana would lead a march on Islamabad. And not just any March, but one four-million strong.

Qadri’s deadline runs out soon. The Occupy Islamabad stunt was scheduled for Monday. His votaries, it is threatened, will not disperse until the maulana’s demands are accepted. Tahrir Square has been cited as an example. And it has lately been announced that half the flock could be diverted to Lahore in view of the Punjab government’s hostility.The Islamabad March will be peaceful, but Qadri has pre-emptively refused to take responsibility for the actions of his followers in the Punjab capital.

In his December 23 speech, he also endorsed a role for the military and the judiciary in setting up an interim government, never mind its unconstitutionality. Qadri subsequently suggested he might, if pushed, accept the post of interim head of government, but later recanted.It is hardly surprising that most commentators have questioned his credentials as well as his motives. The Pakistan army and US representatives have both denied backing the maulana — but then they would, wouldn’t they?

There is certainly little consolation to be derived from the fact that the initiative of this Canadian citizen, whose reputed moderation as an Islamic scholar and welcome fatwas against terrorism have evidently made him palatable to Washington, is being backed by a British citizen who has this week vowed to unleash a “political drone attack” to which “no one in the country will be able to respond”.The concern is not just that two swallows do not a spring make, but that at least one of them can be certified as a bird of prey while the other’s intentions are open to interpretation as an attempt to revisit the interventions by khaki-clad would-be saviours of yore.

Apart from my encounter via television with the messiah-complex maulana, another highlight of my visit to Pakistan was the political coming-out ceremony of Bilawal Bhutto Zardari on the occasion of his mother’s fifth death anniversary. If it was stage-managed against his will, he tried his best not to let it show, as father and son repeatedly referenced the family ghosts in Naudero.One can only wonder whether he, in quoting Faiz Ahmed Faiz on toppling thrones and tumbling crowns, was obliquely referring to Daddy Z, whom Benazir decreed as her successor “in this interim period until you and he decide what is best”. It’s unlikely the idea of offering her firstborn as a sacrificial lamb crossed her mind, but if it did, she evidently did not put it in writing. – KhaleejNews