Today’s quarterly immigration figures reveal a surprising increase in net migration into Britain driven, not by foreign workers, but by a big rise in the number of students coming to the UK.

Today’s quarterly immigration figures reveal a surprising increase in net migration into Britain driven, not by foreign workers, but by a big rise in the number of students coming to the UK.

While the number of work-related visas issued in the year to June 2010 fell 14% to 161,000, student visas have risen a whopping 35% to more than 360,000.

The figures present a stark reminder of just how difficult it is for government ministers to squeeze immigration without risking damaging the economy.

Foreign students are worth an estimated £8bn to the UK and the fees they pay for their courses underpin the finances of the higher education sector.

Tuition fees paid by overseas students can be up to seven times the price paid by their British counterparts.

Some universities have expressed anxiety that the greater cost and complexity of getting a student visa these days has put off many young people who had considered buying courses in Britain, although today’s data suggest the tougher arrangements have not had a detrimental effect.

In fact, it appears that the UK’s academic institutions are holding their own in an expanding and immensely lucrative international market.

There will be concerns that the big rise in foreign students coming to Britain is driven by young people whose interest is economic rather than academic. There is some evidence that this does happen but the controls have been repeatedly tightened.

Since February anyone wishing to study in Britain must first obtain a formal invitation from one of nearly 2,000 colleges on a register run by the Home Office.

Those taking a course below degree level must go through an institution on what is called the Highly Trusted Sponsors List, they must have English to a level just below GCSE, they cannot work and they cannot bring dependants into the country. The visa costs £199.

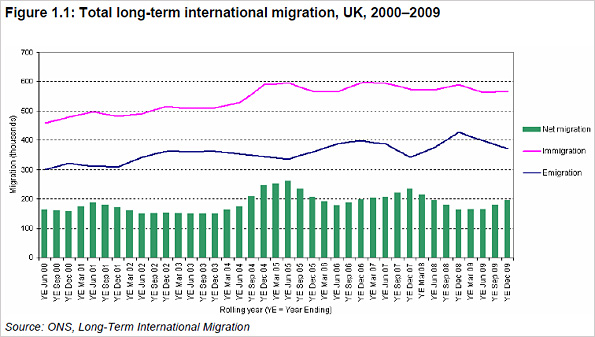

The net immigration figure in the year to December 2009 has risen to 196,000, compared with the final estimate of 163,000 in the year to December 2008. This graph shows how a fall in the number of people leaving Britain and a relatively stable immigration picture has resulted in the rise.

What the graph does not show is that the fall in emigration is driven largely by a reduction in the number of Brits leaving the country – the “number of non-British citizens emigrating long term from the UK was 211,000, not statistically significantly different from the estimate of 243,000 in the year to December 2008”.

To understand how the different categories of people coming into Britain have changed over the past decade, this graph provides a neat picture.

The squeeze on temporary employment visas and skilled workers from outside the EU (tier two) is clear, as is the huge increase in the numbers of student visas issued.

It is worth pointing out, of course, that student visas are temporary. Once the individual has completed their course they are normally required to leave the country without delay. Some may stay on, hiding from the authorities as an illegal immigrant, but the vast majority will return home unless they have a job and a new work visa to go with it.

So if the coalition sticks to its guns on reducing the net immigration figure to below 100,000, today’s figures show that the job just got a bit harder – BBC