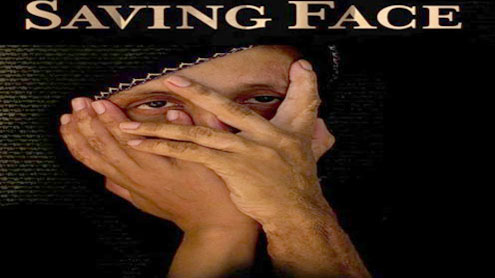

Saving Face is an important moral victory for us and not for ‘them’, whoever ‘they’ may be. The makers behind it are great ambassadors for Pakistan, making people all over the world notice that there are people who are actually striving towards the betterment of our society.

It is funny how one remembers the details afterwards. How Melissa McCarthy struggled opening the envelope, how Morgan Freeman did not applaud and most importantly, how the word Pakistani was mentioned several times in the acceptance speeches. It is only fitting, because Daniel Junge and Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy’s Academy Award-winning documentary short, Saving Face, is a documentary about details.

It’s not the kind of details that are laid out, but it is rather the kind of details that one has become accustomed to. Yes, the sick part of our society has become a part of us and Saving Face merely highlights this fact; how to deal with whatever that may be is something for us to find out by ourselves.

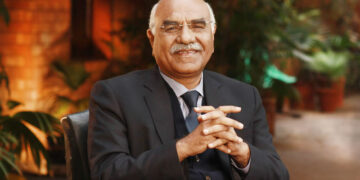

Saving Face is about Dr. Mohammad Jawad, a plastic surgeon from London, who comes to Pakistan to perform surgeries on selective acid attack survivors, all female. The doctor, who is affable and instantly likeable, is not new to these kinds of operations; he had a big hand in partially restoring the face of former British model Katie Piper, who was a victim of an acid attack in 2008.

The documentary takes a close look at the lives of these women who have little to no self-confidence and they explain under what circumstances they were subjected to these heinous crimes. The Acid Survivors Foundation for Pakistan tries its best to give these women back their dignity and the scene featuring the roundtable conversation early on is a heartbreaking one. Another important issue the documentary looks at is parliament’s decision to pass a new bill on acid violence. The film’s main subject, Zakia, eventually becomes the first person to successfully convict her husband in a case of acid violence.

Why Saving Face is such a good documentary is because it almost plays out more like a social drama than a documentary. It has been edited smartly (by Davis Coombe and Hemal Trivedi), especially when Dr. Mohammad Jawad first meets a patient. There is a look of disbelief on his face, but he does his best to maintain his professionalism. These two characteristics reflect the surreal nature of the situation he is in. The same patient later tells her husband, over the phone, that she’s pregnant, but he, the husband, doesn’t seem too interested in that news.

As soon as the film won the Academy Award for best documentary short, cynics and naysayers started declaring this win, an important one for Pakistan, as a conspiracy. What is a conspiracy really? The word has been used so often with everything related to Pakistan, that now it almost seems like a pseudo-term. Who conspired against whom? Did Dr. Mohammad Jawad, the plastic, reconstructive and burns surgeon have an ulterior motive other than giving a woman her dignity back? Did Daniel Junge, the American filmmaker who initiated this project, think of defaming Pakistan by showing that acid attack victims in our country are living a life of silent suffering? Or did Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy see an opportunity to ‘exploit’ this issue to her own advantage?

All these points are best answered by Dr. Jawad, a Pakistani himself, towards the ending of the documentary:“…In a way, I’m saving my own face. Because I’m part of this society, which has this disease. And I’m doing my bit…but there’s only so much I can do…come join the party.”

If one looks at her filmography, Obaid-Chinoy has always chosen subjects that expose certain problems of a society. A filmmaker shouldn’t be questioned for his or her choices, as long as the content is qualitative. Sure, these issues are often hard to digest because they raise questions and not answers but it’s just the nature of the worlds that Obaid-Chinoy chooses to explore. An earlier film of hers, Transgenders: Pakistan’s Open Secret, is commendable because it’s daring, maybe even more so than Saving Face. Playing as part of the Tongues on Fire London Asian Film Festival programme in March 2012, the documentary tells the story of Karachi’s transgender community through three main subjects, who all dream of a better life but have to fight for being deemed as nationals. If one were to compare the two documentaries, Saving Face ends on a more positive note, whereas Transgenders ends on a much bleaker one.

There will always be critics, but in all fairness, the film will have to be released in Pakistan as soon as possible for people to realise that it really isn’t harmful to this country’s image. Winning an Oscar is just a by-product. In fact, Saving Face is an important moral victory for us and not for ‘them’, whoever ‘they’ may be. The makers behind it are great ambassadors for Pakistan, making people all over the world notice that there are people who are actually striving towards the betterment of our society. There’s only so much these people can do though. Ultimately, we’ll all have to ‘join the party’. – Dailytimes